Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

The co-authors of a recent article in Foreign Affairs, America Could Lose the Tech Contest With China, Eric Schmidt and Yll Bajraktari, are Chair and CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP), respectively. The SCSP “builds on the work of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI), which ended its congressionally-mandated work in October 2021. NSCAI made recommendations to the President and Congress to “advance the development of artificial intelligence, machine learning and associated technologies to comprehensively address the national security and defense needs of the United States.”

The SCSP is a bipartisan, non-profit initiative with a clear mission: to make recommendations to strengthen America’s long-term competitiveness for a future where artificial intelligence (AI) and other emerging technologies reshape our national security, economy, and society…to ensure that America is positioned and organized to win the techno-economic competition between now and 2030, the critical window for shaping the future.” (1)

Schmidt and Bajraktari begin their article by itemizing what they call the “reactive approach…on the technological battlefield” to the Chinese challenge to date:

The author’s diagnosis of the root cause of the problem is aligned with the drivers behind the recent launch of America’s Frontier Fund and the Quad Investor Network (with which Eric Schmidt is also affiliated) and maps to many of the recent “Deep Tech” and “Valley of Death” discussions here at OODA Loop:

Strategically, the authors call for:

In the realm of policy and regulation, the authors call for a “balanced approach” to achieve competitive advantage through:

The following section of the article is, at the very least unique, and I would argue somewhat unprecedented, in the specificity of the strategic technological recommendations made by a non-profit think tank to the U.S. military and the U.S. intelligence community:

The tone of the recommendations in this article by Schmidt and Bajraktari should not be surprising, as the recent work of the NSCAI and the launch of America’s Frontier Fund and The Quad Investor Network are all of a whole – and represent the private sector staying engaged and formalizing their commitment to these strategies after their initial engagement with the delivery of the report from the NSCAI. In many sources we have reviewed, Eric Schmidt is credited with the realization that the private sector has to stay engaged in a real ‘sleeves rolled up”, actionable manner, which resulted in the creation of the SCSP.

This recent article in Foreign Affairs is also a part of a public relations campaign related to the recent release of the SCSP 189 page report, Mid-Decade Challenges for National Competitiveness. At such a length, there is much to review in this report. The strategy, policy, regulation, military, and IC recommendations included in the article by Schmidt and Bajraktari have their origins in this report and essentially act as an Executive Summary of the report.

Following are further high-level highlights from the report:

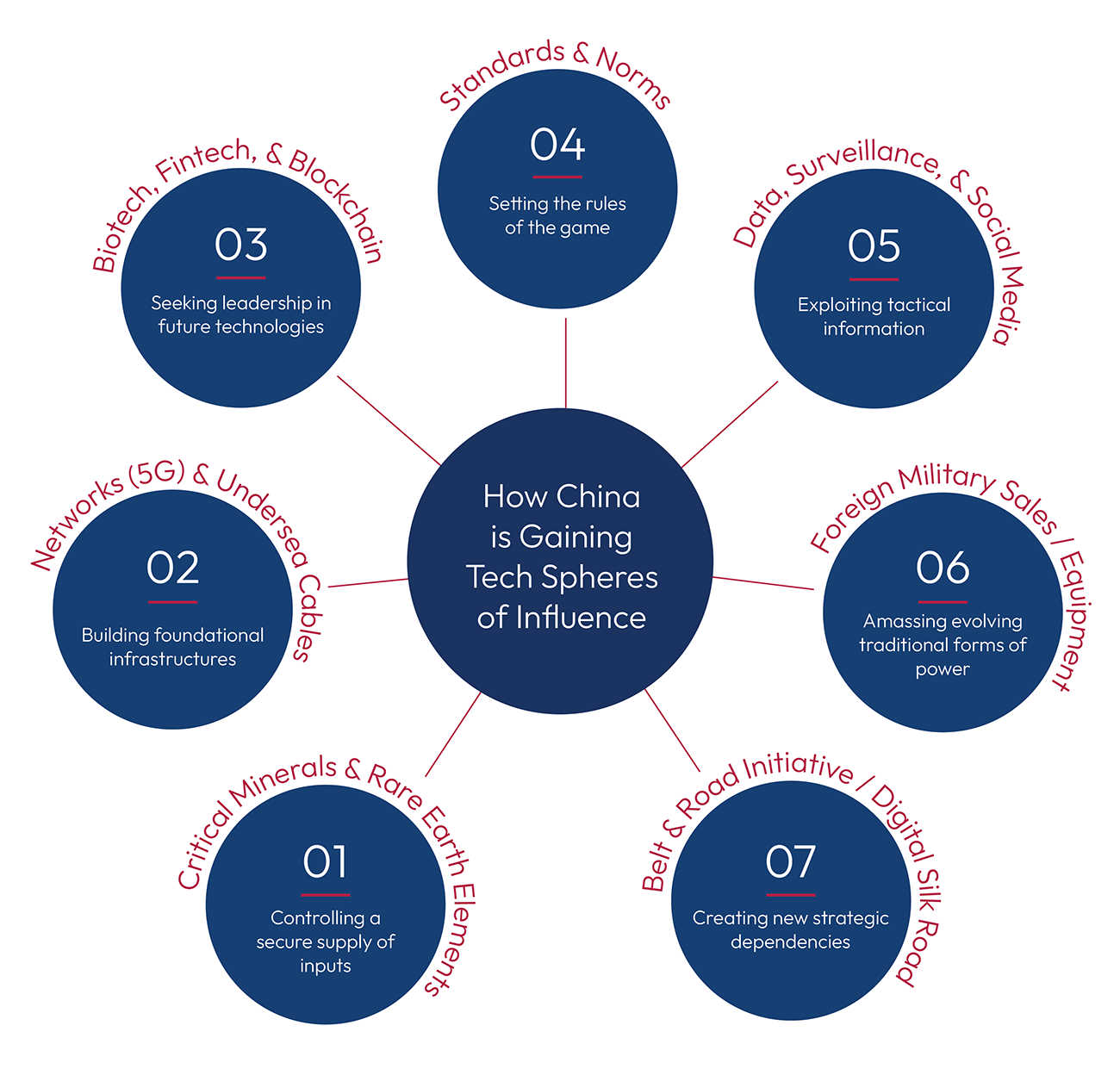

China’s Growing Tech Spheres of Influence. China’s tech advantages are translating into strategic impact through the classic idea of spheres of influence applied through new methods and in new domains. China’s spheres of tech influence range from control of critical inputs like rare earth minerals to network infrastructure through its Digital Silk Road projects, strategic approach to international standards bodies, and export of surveillance technologies. This tech influence is translating to geostrategic leverage around the globe as countries dependent on China vote differently in international bodies, change their position on Taiwan, and toe the PRC’s foreign policy lines on issues ranging from human rights to cyberspace norms.

The United States can be on a winning path by the middle of the decade if it can solve six challenges. The cumulative answer to how we address these challenges constitutes an agenda for restoring America’s competitiveness:

Challenge 1 – Harnessing the New Geometry of Innovation: How can we unlock and connect the expertise, will, and resources that exist throughout American society to build national advantages in critical technologies? The United States’ strengths across its commercial, academic, and government sectors are not oriented toward international competition. Our proposed answer is a new public-private model – one that provides a focused strategy process for the United States to deploy in making informed judgments on national technology priorities and for creating action plans to accelerate the tech applications.

Challenge 2 – Restoring the Sources of Techno-Economic Advantage: How do we ensure that the United States remains the world’s most dynamic, competitive, and resilient economy in the 2020s? America’s advantages across its innovation ecosystem, workforce, and financial sector mean the economic competition should be America’s to lose. Today, however, the erosion of American manufacturing combined with the PRC’s techno-economic advance has triggered anxiety that the American system lacks resilience and cannot convert its advantages into national power. As Chapter 2 elaborates, to stay ahead, the United States needs a techno-industrial strategy that increases economic output and fills economic and national security gaps.

Challenge 3 – An American Approach to AI Governance: How can we develop a technology governance regime that protects the rights of individuals and still unlocks the power of innovation to improve society? All societies are searching for models of technology governance that enhance global competitiveness by propelling innovation while also accounting for risks and vulnerabilities. The EU is building a regulatory framework. China is pioneering a techno-authoritarian model. The search for an American model, outlined in Chapter 3, takes place in this global context.

Challenge 4 – Remaking U.S. Global Leadership in the Age of Tech Competition: How can we preserve an open international order, underpinned by respect for sovereignty and trusted digital infrastructure, that meets the aspirations of the widest number of people and is still guided by democratic values? Chapter 4 traces technology’s place at the heart of the long-term contest between democracy and authoritarianism. The PRC is pursuing a methodical approach to build technology spheres of influence from which it can coerce political preferences. Its strategy rests on controlling the global digital backbone, providing useful platforms and services, and setting international tech standards. The United States and its allies must marshal the resources and diplomatic efforts to compete across the world so nations have real choices about their futures.

Challenge 5 – The Future of Conflict and the New Requirements of Defense: In the face of military rivals employing new technologies and operational concepts to gain advantage, how can the United States ensure a favorable global balance of military power, and uphold its defense commitments in the event of aggression? A strong military deterrent to keep the peace is a necessary precondition for pursuing a positive agenda. Chapter 5 sketches the interplay of new technologies and traditional geopolitical rivalry that are producing a dangerous set of international conditions.

Challenge 6 – Intelligence in an Age of Data-Driven Competition: How can the United States win the race for actionable insight in an information-rich and geopolitically-competitive world? Out-knowing authoritarian rivals is a critical advantage in strategic competition. Chapter 6 describes how the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) will have to master emerging technologies to deliver relevant and timely insight to decision-makers and augment its efforts by focusing on foreign technology developments shaping military, economic, and political trends. (2)

Many of the technological challenges and strategic Great Power competition implications addressed by Schmidt, Bajraktari, and the SCSP report will be discussed (when we gather as the OODA Community in October at OODAcon 2022 – The Future of Exponential Innovation & Disruption) in the context of the following panels:

Tomorrowland: A Global Threat Brief

Bob Gourley, CTO of OODA LLC | Former CTO at Defense Intelligence Agency

Johnny Sawyer, Founder of the Sawyer Group | Former Chief of Staff at Defense Intelligence Agency

The Pandemic, Russian invasion of Ukraine, demographic inversions, and technological labor force disruption have combined to forever shift the global geo-strategic environment. This session will examine the new world economy, seeking actionable insights for practitioners who need a deeper understanding of new realities. Impacts on individuals, investors, businesses, the military, and governments will be examined.

Swimming with Black Swans – Innovation in an Age of Rapid Disruption

Dawn Meyerriecks, Former Director of CIA Science and Technology Directorate

If Yogi Berra were to evaluate today’s pace of global change, he might simply define it as “the more things change, the more they change”. Are we living in an exponential loop of global change or have we achieved escape velocity into a “to be defined” global future? Experts share their thoughts on leading through unprecedented change and how we position ourselves to maintain organizational resiliency while simultaneously reaping the benefits of new technologies and global realities.

The Future Hasn’t Arrived – Identifying the Next Generation of Technology Requirements

Neal Pollard, Former Global CISO at UBS | Partner, E&Y

Bobbie Stempfley, Former CIO at DISA | Former Director at US CERT | Vice President at Dell

Bill Spalding, Associate Deputy Director of CIA for Digital Innovation

In an age when the cyber and analytics markets are driving hundreds of billions of dollars in investments and solutions is there still room for innovation? This panel brings together executives and investors to identify what gaps exist in their solution stacks and to define what technologies hold the most promise for the future.

Postponing the Apocalypse: Funding the Next Generation of Innovation

Matt Ocko (invited), DCVC

What problem sets and global risks represent strategic investment opportunities that help reduce those risks, but also ensure future global competitiveness in key areas of national defense? This session will provide insights from investors making key investments in these technologies and fostering future high-value innovation.

Open the Pod Bay Door – Resetting the Clock on Artificial Intelligence

Mike Capps, CEO at Diveplane | Former President at Epic Games

Sean Gourley, CEO and Founder at Primer.AI

Artificial intelligence is like a great basketball headfake. We look towards AI, but pass the ball to machine learning. But, that reality is quickly changing. This panel taps AI and machine learning experts to level-set our current capabilities in the field and define the roadmap over the next five years.

To register for OODAcon, go to: OODAcon 2022 – The Future of Exponential Innovation & Disruption

It should go without saying that tracking threats are critical to inform your actions. This includes reading our OODA Daily Pulse, which will give you insights into the nature of the threat and risks to business operations.

Use OODA Loop to improve your decision-making in any competitive endeavor. Explore OODA Loop

The greatest determinant of your success will be the quality of your decisions. We examine frameworks for understanding and reducing risk while enabling opportunities. Topics include Black Swans, Gray Rhinos, Foresight, Strategy, Strategies, Business Intelligence, and Intelligent Enterprises. Leadership in the modern age is also a key topic in this domain. Explore Decision Intelligence

We track the rapidly changing world of technology with a focus on what leaders need to know to improve decision-making. The future of tech is being created now and we provide insights that enable optimized action based on the future of tech. We provide deep insights into Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Cloud Computing, Quantum Computing, Security Technology, and Space Technology. Explore Disruptive/Exponential Tech

Security and resiliency topics include geopolitical and cyber risk, cyber conflict, cyber diplomacy, cybersecurity, nation-state conflict, non-nation state conflict, global health, international crime, supply chain, and terrorism. Explore Security and Resiliency

The OODA community includes a broad group of decision-makers, analysts, entrepreneurs, government leaders, and tech creators. Interact with and learn from your peers via online monthly meetings, OODA Salons, the OODAcast, in-person conferences, and an online forum. For the most sensitive discussions interact with executive leaders via a closed Wickr channel. The community also has access to a member-only video library. Explore The OODA Community.