Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

A few decades from now, historians might conclude we are living in a Second Gilded Age. In a bit of a repeat of the 1890s, our mid-2020s seems to be an era where technological advancements have triggered fear and uncertainty about what the application of those technologies means for workers, industries, and nations. Massive polarization of politics was present in the 1890’sand the beginning of the 1900s, with the United States Congress slightly more polarized than our current era. Similarly, a push-and-pull over regulation of technological advancements during the First Gilded Age mirrors some of what we see now amid our Generative AI (GenAI, defined as machines able to generate synthesized media from data training sets).

Now the United States and countries around the world are facing another wave of technological evolutions and disruptions, to include the latest advancements in commercial space capabilities, biotech and synthetic biology, quantum technologies, Internet of Things sensors, as well as Artificial Intelligence. Regarding AI, it’s worth noting that term encompasses a broad swath of technologies and as a field AI itself is not new, it’s been around with various methods since the late 1950s and we may well discover the current wave of GenAI, dependent on Deep Learning, proves to be an energy- and data-intensive dead-end to be replaced with other methods. While advances in computing power, along with a sheer abundance of digital data now present online, result in the increase effectiveness of AI algorithms from the 1980s and 1990s, we would be remiss if thinking doubling-down in current regime of AI will achieve what we want for communities, companies, and citizens alike; Deep Learning may have its limitations both in terms of usefulness if the present or near-future differ from the past training data sets and in terms of the inability to implement safety controls prior to the AI doing some form of compute actions.

like the First Gilded Age, there is significant fear and uncertainty about what the application of those technologies means for workers, industries, and nations – as well as a dramatic uptick in misinformation and disinformation. Lest we forget, the 1890s saw Yellow Journalism and the “Remember the Maine!” moment tied to the U.S. ultimately going to war with Spain.

Like the First Gilded Age, we also have the rise of cult-like movements – whereas the 1890s saw an obsession with the occult and seances to communicate with the dead, now there are some who either claim “machine consciousness” is right around the corner or impending doom is nigh as AI becomes ever more capable. Virtue signaling is high, with some movements believing that by focusing on perceived (though immeasurable) existential threats of doom, we can somehow prevent potential catastrophes, even as here-and-now injustices, harm, and disruptions happen to people on an everyday basis with the existing technologies.

In short, amid the backdrop of different technological revolutions happening, there is no shortage of perceived problems with the most extreme voices capturing the largest amount of airtime and attention. A substantial risk exists of amplifying learned helplessness, where individuals feel like there’s nothing to be done that will work given the sheer challenges of a topic, as well as cognitive easing, where repetition of these doom-focused narratives makes folks more likely to believe them even if the underlying assumptions and risks warrant closer examination – resulting ultimately in limited, ineffective solutions to these potential problems.

What’s missing are operational places to bring together the public, private sector organizations, universities, government agencies, and non-profits to seriously work on systematically solving some of these problems. This approach is especially true for the class of problems tied to misuses and abuses of GenAI.

Several pundits around the world presently seem to think AI can be designed more safely – and perhaps to a degree it can. However, it should be clear that if AI can be designed more safely, it also can be designed more dangerously and weaponized. Both law enforcement and national security professionals know, given what they already see daily, that there surely will be bad actors who opt to remove any guardrails from AI if they can profit from it or weaponize it in ways similar to how cars were used for interstate crime in the 1900s. When considering our now, we would do well to remember when most of the nations of Europe, after promising not to pursue chemical munitions in 1899, quietly did indeed do this in the build up to WWI and employed such weapons within the first year of that war.

The ”AI plus bio will result in doom” narrative seems to miss that AI-generated knowledge of something is not synonymous with experience in doing something. Medical students who read textbooks are not ready to do open heart surgery without significant training and experiences leading up to this. Just because a Large Language Model (LLM) can provide information on, say, how to do surgery – does not mean individuals employing such an LLM are ready to practice surgery yet. AI already is rapidly being democratized, with hardware presently more a limitation than anything else on the scale of which it can be run – a barrier that will be temporary at best as computing advances improve. Furthermore, Deep Learning as an algorithmic approach, in addition to potentially becoming energy- and data-intensive dead-end to be replaced with other methods, may be fundamentally unsecureable precisely because it has no a priori rules or axioms other than the data used to train the AI, meaning any filters occur post-processing vs. other AI approaches that could feature pre-processing bounding restrictions and restrictions that occur as the AI itself does digital inferences.

Einstein famously said: We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Even if AI somehow leads to new threats associated with what might be possible with biotech, then the correct response would not be to look for a technological fix to contain the technology because any such attempts might risk censoring AI or miss the reality that some bad actors will still find ways to weaponize AI systems. Containment of AI models or data censoring represent technical attempts to what are system-level concerns, and technical fixes alone will not work in the long-term. Instead of consuming precious policymaking and researchers time on “AI plus bio will result on doom” activities, imagine if instead we looked at how we could instrument the planet in a privacy-preserving fashion to detect, respond faster to, and protect humans and animals from pathogens both natural and human-made, including any such bioagents added by AI?

Such a systems-level solution is already needed, given that we clearly just had a pandemic, and now an emergence of H5N1 the agricultural sector of the United States. In addition, near-term climate change will result in more natural pathogens showing up in abnormal ways as we adapt to our changing world, as early evidence of ice sheet melting has demonstrated the risk of previously frozen sources of biological material re-emerging.

Similarly, if the far-off future we have designer cells and related biological material that can be customized both to provide personalized medicine – which would be a net positive – and if misused or abused result in personalized poison, then the solution to these challenges will be as it always has been. We will need a systems-level, whole-of-society approach to detect and respond faster to novel pathogens both to protect innocents as well as deter bad actors. Such approaches had to rally and come together when other disruptive technologies impacted societies in the past, and it’s something humans do best when we realize we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Furthermore, while it is well and good to turn to AI companies and AI labs to strive to see if AI can be made safer, this approach is tantamount to turning to the same thinkers who have presented the current challenges the world faces. As an example, the answer to the risk of fire in cities and more dense populations required systems-level solutions, to include designing buildings better, fire code inspectors, clear liability rules for those who didn’t follow fire code practices, and ultimately smoke detectors and radio dispatch of fire fighters faster to deal with fires. Clear liability rules also helped to hold people responsible if their inaction or intentionally bad actions harmed people.

As another example, when the disruptive technology of amateur radio arose and presented the risk of radio being used by spies transmitting information out of a country in the build-up to World War II, the systems-level solution included requiring licenses for amateur radio operators, an enforcement division (at the time named the Radio Intelligence Division), and clear liability rules for misuse and abuse.

We need to recognize turning to AI companies to make AI safer is turning to the “same thinking” that Einstein warned against. A recent Science article observes that:

In 2000, Bill Joy warned in a Wired cover article that “the future doesn’t need us” and that nanotechnology would inevitably lead to “knowledge-enabled mass destruction”. John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid’s criticism at the time was that “Joy can see the juggernaut clearly. What he can’t see—which is precisely what makes his vision so scary—are any controls.”

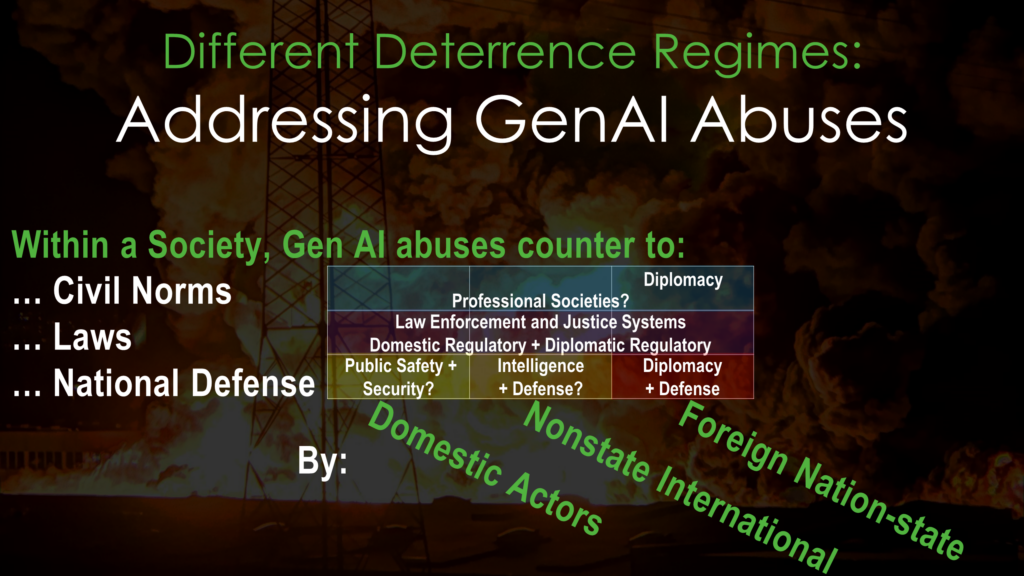

If we approach For GenAI, three clear domains exist in which whole-of-society controls can be implemented by societies, in ways that aren’t dependent on censoring data sets or assuming that safer AI won’t be made unsafe by actors. These three domains include deterrence actions countering misuse and abuse of GenAI tied to national defense, law enforcement, and civil norms of societies – specifically from bad actors associated with domestic actions, non-state international entities, or foreign nation-states.

In addressing GenAI abuses, be they abuses that harass, defame, or emotionally hurt individuals or the ones that damage or destroy critical infrastructure or operations of societies – deterrence must demonstrate credible “costs” to deter human actors, must be able to correct attribute and reach bad human actors, and must be done in a manner where free societies do not lose public trust and support while defending the public from these potential harms. This would need to include demonstration of controls for unknown uses of democratized technologies, as bad actors can and will use benign items in creative ways (breaking glassware can result in a deadly weapon, for example).

Furthermore, systems-level thinking across these three domains of potential GenAI misuse and abuse, done by three distinct types of bad actors, indicates the need for solutions involving public safety and security, intelligence and defense, diplomacy and defense, law enforcement and justice systems, domestic regulation, diplomatic regulation, as well as professional societies. Ultimately, what is needed is the combination of norms, laws, and defensive actions operating in concert to protect against AI misuses and abuses emanating from nation states and non-state actors.

Creative systems-level solutions can include a multi-nation triangulation and attribution alliance to counter GenAI abuses tied to national defense, as well as random citizen juries, with a similar set of constrains to whole-of-society challenges, as part of oversight mechanisms to ensure public trust is not lost as publics are protected. Similar solutions for GenAI abuses tied to breaking laws include clear liability regimes and bilateral/multilateral agreements with other nations for cross-border criminal investigations, as well as a clear convention spelling out the rights of people to be free of AI abuse or unintended impact while simultaneously ensuing such activities do not result in a surveillance state in response to GenAI risks. Finally, systems-level solutions for GenAI abuses tied to breaking civil norms must avoid a heavy-handed approach that forces AI underground, could potentially emulate the “ham radio licenses” regime of the past, and include professional societies to license and credential certified ethical data scientists and GenAI developers in ways akin to the responsibility of Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) to act in the best interest of the public, not solely the employer paying their salary.

Nobel-prize winning Herbert Simon, one of the forefathers of modern AI, wrote a book about the Sciences of the Artificial in which he observed that not only is AI an artificial phenomena of our creation, but so is civil society and by extension all that we do to protect civil norms, laws, and national defense to include actions we do to deter bad actors from misusing and abusing tech in these domains.

We can use systems-level thinking to address head-on the issues of both today and the future if we work to create places in public service where we can collaborate with citizens and private sector partners to develop new ways to conduct the business of public service as well as deter bad actors that misuse and abuse GenAI.

In short, all is not lost. Yes, Houston, we may have a problem… so let’s get to solving it with systems-level thinking instead of either extreme doom thinking (that misses both the here-and-now problems needing action as well as solutions we can do) or technology-only thinking that misses whole-of-society activities that can be enacted and improved. Moreover, the option to “wait and see” is a false choice – the world continues to move, and us with it. Here’s to tackling these issues head-on with whole-of-society, systems-level approaches.

Dr. David Bray is both a Distinguished Fellow and co-chair of the Alfred Lee Loomis Innovation Council at the non-partisan Henry L. Stimson Center. He is also a Distinguished Fellow with the Business Executives for National Security, Fellow with the National Academy of Public Administration, as well as a CEO and transformation leader for different “under the radar” tech and data ventures. David has received both the Joint Civilian Service Commendation Award as well as the National Intelligence Exceptional Achievement Medal and served as the Executive Director for two National Commissions involving advances in technology, data, national security, and civil societies. He has been a fan of Bob Gourley and OODAloop ever since Bob and he did a panel together on what new technologies mean for the U.S. Intelligence Community in 2008.