Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

Two of the clear strategic playing fields for competitive advantage are the future of battery production and high-performance computational capabilities. In both cases, rare earth minerals – crucial to the production of everything from semiconductors to electric vehicle (EV) batteries – are the critical risk factor in the future of a green global economy and emerging technologies.

Geography and geopolitics matter when it comes to sourcing these materials, especially any future supply chain dependencies on other countries, including potential adversaries. Japan is getting its own strategic house in order – and is stepping up its efforts to access regional rare earth resources in a bid to challenge China on a variety of fronts.

“Like most nations, Japan would prefer to use its organic resources to fill these requirements…”

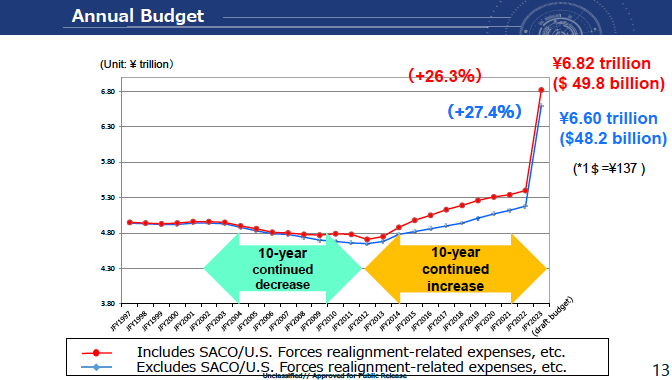

OODA’s Chris Ward recently reported that in its “national military strategy Last December, Japan dramatically transformed its National Defense Strategy, committing to increasing defense investments to 2% of the GDP by 2027. Their recently published Defense Buildup Program sets mid-term (5-year) and long-term (10-year) goals, allocating $314B (in US dollars) – a 1.6X increase. The below chart has been presented by the Japanese Ministry of Defense at multiple forums this year:

Investments will be allocated to seven key defense capability areas:

Like most nations, Japan would prefer to use its organic resources to fill these requirements. However, considering the long prohibition against military-specific investments, Japan realizes that quickly achieving these goals will be difficult without imported key technologies and rapid acquisition capabilities. To that end, they are standing up (later this year) a new organization, modeled after our DARPA or Defense Innovation Unit, that can work with Industry to quickly bring together new defensive capabilities. (1)

“…clear prioritization will be critical to ensuring resources are used effectively and not spread thin…”

Jeffrey W. Hornung and Christopher B. Johnstone, in their recent WAR ON THE ROCKS (WOR) commentary – Japan’s Strategic Shift Is Significant, but Implementation Hurdles Await – War on the Rocks – further captured the strategic landscape in Japan:

[In December 2022], the Japanese government released three landmark strategic documents: the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Plan. Collectively, they represent pathbreaking change and may signal that Tokyo not only shares a common strategic vision with the United States but is also committed to do far more for its own defense.

Japan’s post–World War II defense policy has been defined by incrementalism and inelasticity. Beginning in the 1970s, Tokyo had a tendency to constrain defense spending to 1 percent of GDP. After the country’s economic bubble burst in the mid-1990s, Japanese economic growth slowed significantly — and Japanese defense spending effectively stagnated as a result. Spending in 2021 was just 9 percent higher than the level almost 25 years earlier. Tokyo’s announcements on December 16, therefore, signify an inflection point, both in the volume of planned defense investments and the capabilities the country intends to acquire. Together, these changes reflect an evolved concept of deterrence for Japan and what is required to sustain it, and once implemented they could result in a much more capable U.S. ally and critical force multiplier.

With complaints in Washington throughout most of the post–Cold War era that Japan’s security contributions were not commensurate with its economic stature, this newfound demonstration of commitment represents a significant step forward for Japan. If it follows through on its plans, Japan could emerge as a formidable defense actor over the next 10 years. All of this is good news for the U.S.-Japan alliance, given the increasingly important role Japan plays in Washington’s national security and defense strategies. Yet, even with a significant growth in spending — a planned nearly 60 percent increase in the defense budget over five years — clear prioritization will be critical to ensuring resources are used effectively and not spread thin across competing areas of focus.

Describing Japan’s security environment as “the most severe and complex … since the end of World War II,” Tokyo’s national security and defense strategies set out plans for unprecedented change…

…While the Japanese government insists that the new strategies are consistent with the Constitution and post-war defense strategy, they nevertheless reflect an important evolution in Japan’s approach to defense and deterrence that traditionally focused on striking forces engaged in an armed attack against Japan itself. Today, while Japan’s strategy is still anchored on its defense, its deterrent focus is extended far beyond Japanese territory to striking those facilities that could support an attack against Japan. The reasoning behind this is the acknowledgment by Japanese decision-makers that simply relying on air and missile defense capabilities alone will prove insufficient should an adversary seek to attack or invade Japan. Counterstrike would give Japan the ability to target military facilities deep in an adversary’s territory, reinforcing deterrence by raising the cost of aggression against Japan. (2)

The Nikkei reports that in 2024, Japan will begin to extract rare earth materials for electric vehicles and hybrids from bottom sea mud in an area off Minami-Torishima Island, a coral atoll in the Pacific Ocean about 1,900 kilometers southeast of Tokyo. The government’s aim is to reduce the country’s reliance on China for rare earth metals.

In a 2018 open-access paper published in Scientific Reports, a team of Japanese researchers noted that deep-sea mud containing more than 5,000 ppm total rare-earth elements and yttrium (REY) content was discovered in the western North Pacific Ocean near Minami-Torishima in 2013. This REY-rich mud has great potential as a rare-earth metal resource because of the enormous amount available and its advantageous mineralogical features:

“Here, we estimated the resource amount in REY-rich mud with Geographical Information System software and established a mineral processing procedure to greatly enhance its economic value. The resource amount was estimated to be 1.2 Mt of rare-earth oxide for the most promising area (105 km2 × 0–10 mbsf), which accounts for 62, 47, 32, and 56 years of annual global demand for Y, Eu, Tb, and Dy, respectively.

Moreover, using a hydrocyclone separator enabled us to recover selectively biogenic calcium phosphate grains, which have high REY content (up to 22,000 ppm) and constitute the coarser domain in the grain-size distribution. The enormous resource amount and the effectiveness of the mineral processing are strong indicators that this new REY resource could be exploited in the near future.

Locality and bathymetric maps of the research area in (Takaya et al.)Star symbols show the piston coring sites and the color-coding corresponds to each research cruise as noted in the legend. The white rectangle shown in the detailed map is the target area where the resource amount estimation was conducted.” (2)

Argus Media places rare earth extraction and the industry sector overall into the Japanese national security strategy in the following manner:

“The Japanese government included rare earth in its National Security Strategy released this month, stating that: “With regard to supply chain resilience, Japan will curb excessive dependence on specific countries, carry forward next-generation semiconductor development and manufacturing bases, secure stable supply for critical goods including rare earth, and promote capital reinforcement of private enterprises with critical goods and technologies, and strengthen the function of policy-based finance, in pursuit of protecting and nurturing critical goods.”

Japan is working to diversify its sources of rare earth supply as its imports have climbed in recent years in line with a rising output of electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, and other products that use permanent magnets.

Japan has long recognised the importance of a diversified rare earth supply chain, after China restricted exports of the metals to the country in 2010 during a political dispute. Japan signed a deal with Vietnam to mine the country’s large deposits, but more than a decade later Vietnam’s domestic production remains limited. China accounts for more than two-thirds of Japan’s rare earth imports, according to Japanese customs data.

Japan is the largest consumer of rare earth such as dysprosium outside China, as the world’s second-largest producer of permanent magnets, with a market share of less than 9pc. China dominates the production of magnets as well as the global supply of rare earth metals and oxides.

The cost of Japan’s rare earth imports has soared in 2022, as Chinese metal prices have climbed. The value of rare earth imports into Japan spiked to ¥9.77bn in June, from ¥2.9bn in June 2021, as spot prices climbed earlier in the year. The value of imports fell from the June high to ¥5.9bn in November, customs data released this week show, but remained far higher than the ¥3bn tallied in November 2021. (3)

Green Car Congress breaks down the report further with some valuable operational and quantitative insights:

Work to develop technologies to extract the resources from depths of 5,000-6,000 meters will begin next year, the report said. The Japan Current—among the world’s fastest sea currents, passes the target area, which is also located in the path of typhoons.

Deep sea oil and natural gas deposits are under strong pressure, which pushes the resources out once a hole drilled from the surface reaches them. However, mud containing rare earth metals does not have this advantage, so it will require some means to bring it up to the surface—pumping, for example.

The Japanese Diet approved an allocation of ¥6 billion ($44 million) for the project in the second supplementary budget for fiscal 2022 recently approved in an extraordinary session. The money will be spent on the development of pumps and making pipe as long as 6,000 meters to be used in trial extraction.

Researchers succeeded in pumping up deposits from a 2,470-meter-deep seabed in a period from August to September.

Japan currently relies on imports for nearly all its rare metal needs, including 60% from China. Japan’s new National Security Strategy announced last Friday states: “Japan will curb excessive dependence on specific countries, carry forward next-generation semiconductor development and manufacturing bases, and secure stable supply for critical goods, including rare earths.” (5)

According to The International Energy Agency (IEA):

In March 2020, the Japanese Government announced a new International Resource Strategy following a public consultation. The resource strategy covers oil and LNG security, critical minerals, and climate change actions.

Regarding critical minerals, a major pillar of the strategy is to reinforce the stockpiling system for 34 types of rare metals covered under the current system, which is authorised under Article III.11(xiii) of the Act on Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC). Under this law, JOGMEC has the authority to implement a national stockpiling program for metallic and other mineral products in order to maintain a stable supply of rare metals in the event of supply disruptions. In general, the specific ore types and quantities for which stockpiles are being held are undisclosed, as disclosure could have a negative impact on the market. To manage the stockpile, JOGMEC subsidises the interest required to borrow funds for the purchase of rare metals and the costs required to maintain and manage stockpile warehouses.

In the 2020 resource strategy, the government announced its intention to review how it sets target volume for stockpiles and to set the target based on national stockpiles alone – i.e. not including industry stockpiles. The target number is generally set at 60 days, but for minerals with high geopolitical risk, it could be set at a higher number “such as 180 days.”

In addition to stockpiling, the resource strategy also announced an intention to strengthen bilateral and multilateral international cooperation through JOGMEC and to strengthen technology development for recycling and the development of by-product materials. The 34 minerals targeted by the stockpiling system include:

The success or failure of decreasing any excessive dependence by Japan on China for rare earth materials will be based on the implementation of the following strategic initiative, market shifts and international partnerships:

WOR’s Hornung and Johnstone conclude with the strategic big picture:

“Japan’s new strategic documents appear to demonstrate a recognition in Tokyo that it must do more for its own defense in the face of unprecedented security challenges. The dedication of resources, the pursuit of new capabilities, and an overarching commitment to a more robust defense are all significant moves that represent landmark change by one of America’s key allies — indeed, one of the most consequential strategic developments in the region in years. As positive as this appears, there is a risk that some ambitions may not be realized — at least on the timeline set out in the documents — due to insufficient resources, manpower, technology, or political will.

As a key ally, it is in the interest of the United States to help Japan address these challenges. The United States can help Japan where possible, through technology support, sales of key equipment, concept, and doctrine development, or more realistic training. It could also work with Japan to help prioritize its efforts to avoid spreading finite resources too thin across all initiatives. Taking these steps now will help ensure that in 10 years the United States finds a more robust defense ally in Japan.” (2)

https://oodaloop.com/archive/2023/04/07/japans-stunning-advancements-in-national-defense-investments/

https://oodaloop.com/archive/2023/04/08/five-more-reasons-japan-should-be-on-your-sensemaking-radar/