Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

Start your day with intelligence. Get The OODA Daily Pulse.

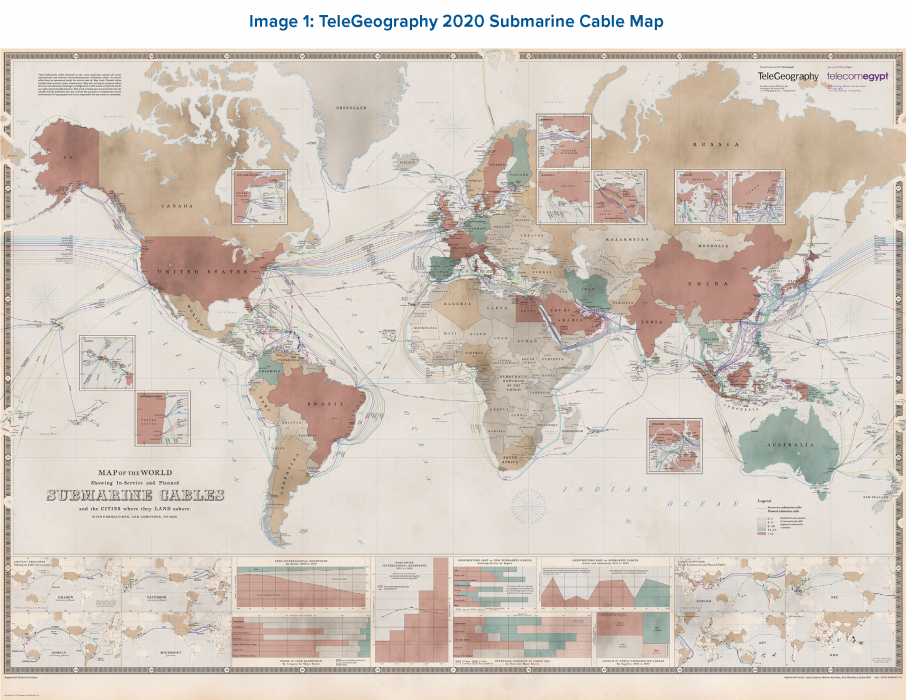

Along with Africa and the Arctic, add the growing tensions between the U.S. and China about undersea cable deployment and seabed warfare to your geopolitical tracking, risk awareness, and strategic impacts for your business or organization. Find an overview of the core issues, tensions, and What’s Next? here.

Image Source: Jayne Miller, “The 2020 Cable Map Has Landed,” TeleGeography Blog, June 16, 2020, https://blog.telegeography.com/2020-submarine-cable-map.

“The goal…is to prevent foreign adversaries…from increasing ownership and control of this key economic and telecommunication infrastructure.”

“…the threat of these vulnerabilities being exploited is growing. … The threat is nothing short of existential.”

Undersea cables have two types of vulnerabilities: physical and digital. The most common threat today is accidental physical damage from commercial fishing and shipping, or even from underwater earthquakes. The U.S. government has studied the security of commercial undersea telecommunication cables in the past. A 2017 report sponsored by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) found that the majority of disruptions are caused by human activity (e.g., fishing, anchoring, dredging) and natural disasters. However, undersea cables could also be targeted by states wishing to sabotage the economies of their rivals:

Some in Congress have expressed concerns over intentional damage to commercial or government-owned undersea telecommunication cables by foreign adversaries and bad actors seeking to disrupt communications or gather personal, corporate, or government information. In 2017, ODNI reported that while there had been few reported attacks on undersea telecommunication cables, some had been long-lasting and impactful. In 2007, Vietnamese pirates stole optical amplifiers, disabling a cable system for 79 days. In 2013, a diver intentionally cut the South East Asia-Middle East-Western-Europe 4 (SMW 4) cable, affecting several service providers,and slowing internet speeds by 60% in Egypt.

The ODNI report stated that signal rerouting technologies, redundancies in cable lines, and networks of repair ships had increased the resiliency of undersea cable networks and reduced the potential that a single cut would cause widespread outages. Further, it asserted that simultaneous attacks against multiple cables could cause “serious long-term disruption,” but are difficult to carry out. Some North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defense officials and other foreign affairs analysts have expressed concern that Russia could cut commercial undersea telecommunication cables to disrupt communications. In 2017, U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Andrew Lennon, commander of NATO’s submarine forces at the time, reportedly stated, “We are now seeing Russian underwater activity in the vicinity of undersea cables that I don’t believe we have ever

seen … Russia is clearly taking an interest in NATO and NATO nations’ undersea infrastructure.”

In 2018, one media outlet, citing a Russian parliamentary publication, reported on Russian capabilities to tap top-secret communication cables, cut undersea cables, and jam underwater sensors. According to an industry expert, “If somebody knew how these systems worked and if they staged an attack in the right way, then they could disrupt the entire system. But the likelihood of that happening is very small.”

Global internet and telecommunications traffic is routed and transported through the undersea telecommunication cable network using advanced information and communication technologies and network management software, making the system vulnerable to cyberattacks. A 2021 think tank report notes that “more companies are using remote management systems for submarine cable networks—tools to remotely monitor and control cable systems over the Internet—which are cost-compelling because they virtualize and possibly automate the monitoring of cable functionality.”

However, these tools (e.g., software, and remote management systems) may create new risks to cable security and resilience. Hackers could access cables through network management systems to skim personal or financial information, hold network management systems hostage until operators pay ransom, or cause widespread disruption in communications. In April 2022, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Investigations (DHSI) reportedly thwarted a cyberattack on a network of a company that manages an undersea telecommunication cable that provides internet and mobile phone services in Hawaii and in countries across the Pacific region.

DHSI officials attributed the attack to an international hacking group, but were not certain of the intent—whether the attacker intended to access business or personal information, hold the system for ransom, or to disrupt communications.69 DHSI reportedly worked with law enforcement agencies in several countries to make an arrest. (1)

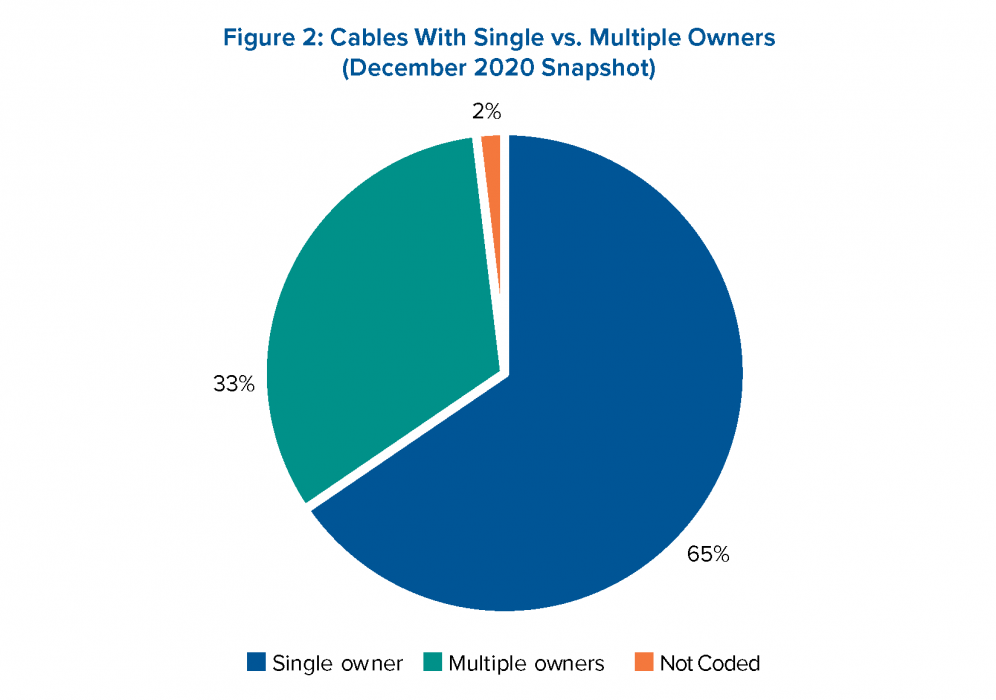

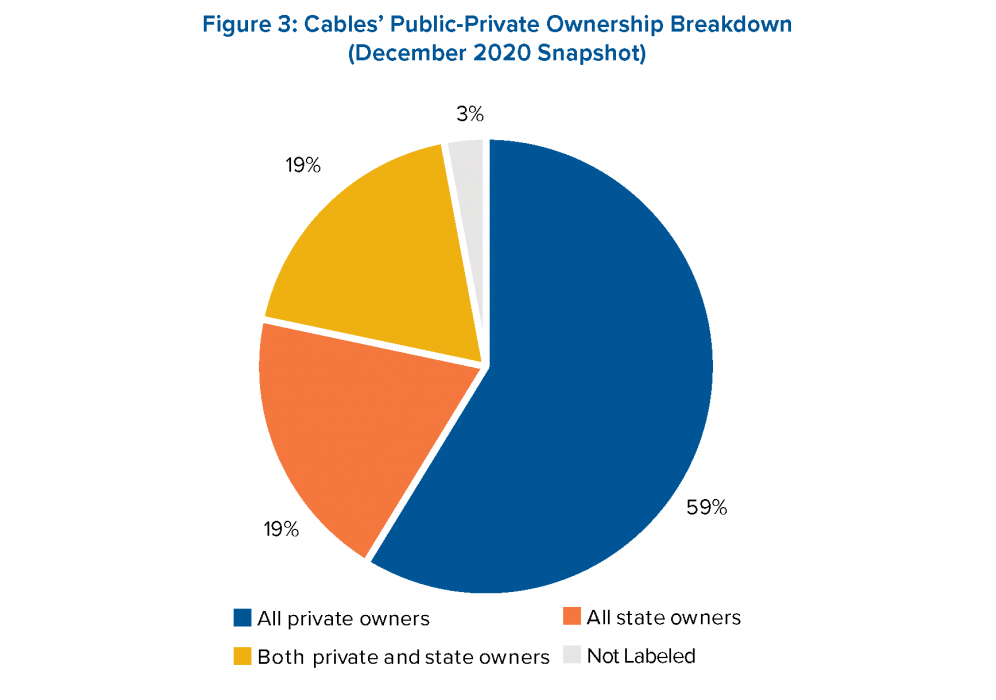

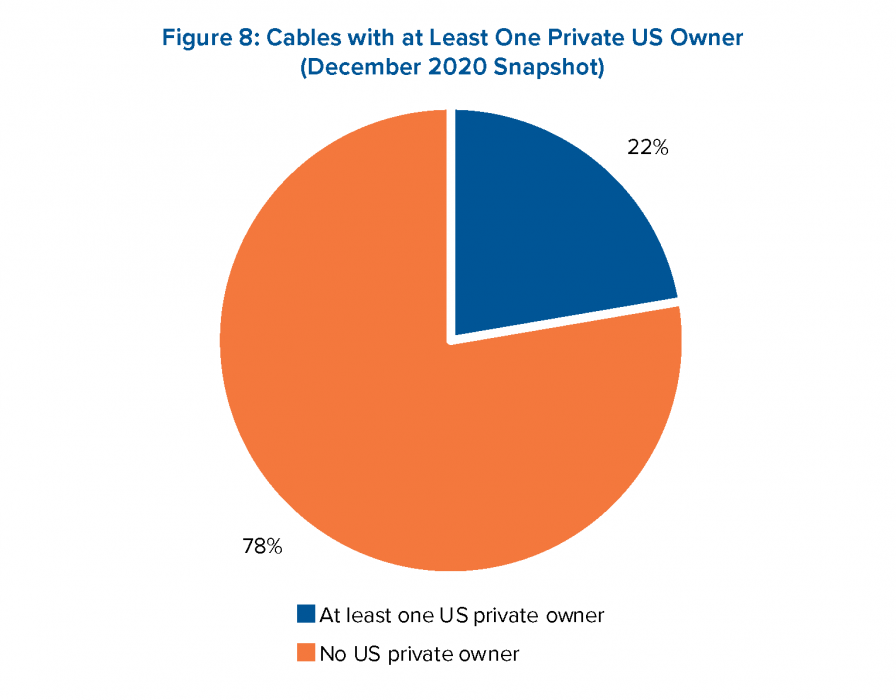

Image Source: Data from TeleGeography’s Submarine Cable Map website – Atlantic Council

Source of Charts: Atlantic Council

As reported by Reuters, with tons of previously unreported information, and definitely worth a full review. You can find the investigative report here. A summary:

Source of Images: reuters.com

Source of Images: reuters.com

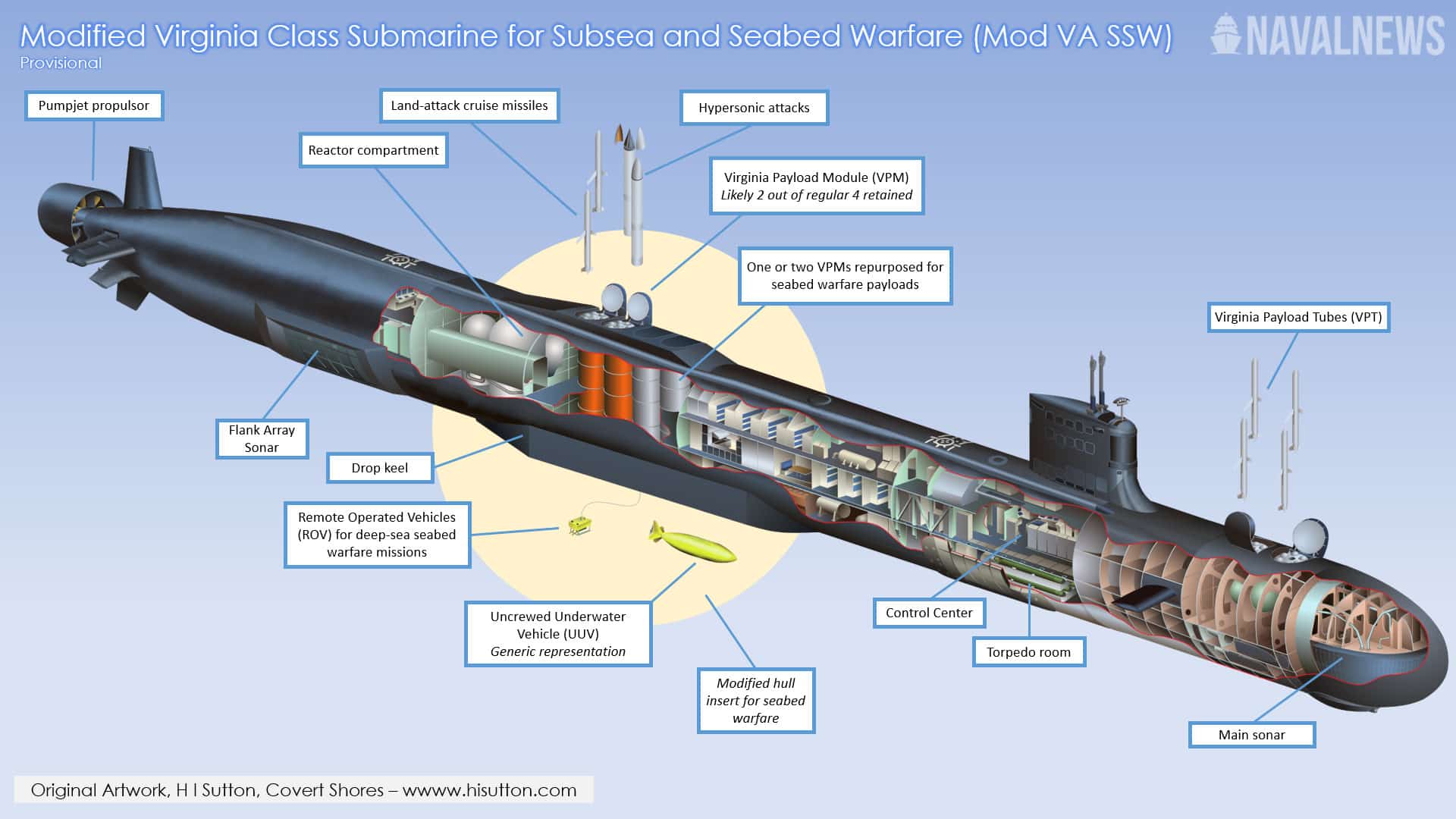

Image Source: Naval News

“And seabed warfare is almost a definition of those three,” Singer said. (5)

Image Source: reuters.com

“The U.S. and its adversaries – especially Russia and China – are scrambling for dominance.”

A report by the Atlantic Council – Cyber defense across the ocean floor: The geopolitics of submarine cable security – offers eight concrete recommendations for the US government, working with the US private sector and allies and partners worldwide, to better protect the security and resilience of the world’s undersea cables:

But even with the influence the US private sector has on global cable development, the private sector cannot go it alone. Poor market incentives for robust security—combined with new threats and an internationally collaborative system of cable construction and management—meaning the US government must also better engage with allies and partners to protect the security and resilience of this submarine cable infrastructure. To this end, [the Atlantic Council] report makes the following recommendations for the US government, along with the private sector and allies and partners, to better protect the security and resilience of submarine cables:

The US Congress should statutorily authorize the US executive branch body responsible for monitoring foreign-owned telecoms in the United States for security risks: the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector (formerly the informal Team Telecom). This would provide it with the necessary funding, review authority, and formal structure to better screen foreign telecoms that own cables. The newly renamed organization is a coordinating entity between several federal agencies, with the FCC playing a key role on the telecom referral and licensing side, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the DOJ playing a key role on the security review side.

The US Congress should conduct a study, starting no earlier than one year into the program’s launch, on the Cable Ship Security Program that was authorized in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2020. The Department of Transportation is currently in the process of standing up the program with two vessels so that government-authorized, privately owned ships are on standby to repair damaged submarine cables relevant to US national security. This program, therefore, helps ensure that alongside commercial investment in cable resilience, the US government is taking steps to repair damaged submarine cables more quickly than they might otherwise be if left entirely up to the private sector.

The US executive branch should create and promote the use of security baselines and best practices for cable remote network management systems. More cable owners are deploying Internet-connected industrial control systems to remotely manage complex cable infrastructure. These systems could be remotely compromised to disrupt or deny the delivery of Internet data across cables, a risk compounded by the poor market incentives for developers of these technologies to legitimately prioritize cybersecurity. As such, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) should create a set of security standards and best practices for vendors that build cable remote network management systems, and for the submarine cable owners that ultimately deploy those technologies at cable landing stations. NIST’s deep technical expertise and widely respected framework-creation process make it well-suited to craft a list of security standards and best practices for the private sector. Then, the US executive branch, particularly large and influential agencies like the Department of Defense, should consider adopting those security baselines and best practices into procurement requirements for any companies doing business with the federal government that also own undersea cables carrying US, and likely US government, data. If the US government is going to have more of its data routed over the global Internet via the public cloud in the coming years, it should be invested in protecting the security and resilience of the remote technologies that manage the underlying infrastructure because their compromise could have serious effects on economic and national security.

The Federal Communications Commission should invest more resources in promoting and maintaining federal interagency cooperation on resilience threats to submarine cables. While this has been an FCC effort for several years now, the growing threats to undersea cable security and resilience make this internal federal coordination an even higher priority. The FCC should focus on such measures as information sharing on resilience threats and continued reassessments of the effectiveness of outage reporting requirements, which were expanded in March 2020. The agency should also work with state and local authorities to integrate cable resilience best practices into permitting decisions, which would create stronger incentives for cable owners to invest in protecting cable resilience. FCC action here can help identify risks, take mitigating steps as necessary, and forge better coordination mechanisms with the private sector (including through ISACs discussed below). Preventing disruptions to cable operation can support the delivery of Internet data and thus economic and national security.

The Department of State should pursue confidence-building measures to strengthen international norms against nation-states damaging or disrupting undersea cables. The political will for any kind of international legal treaty to protect submarine cables is limited: It is difficult to imagine Beijing and Moscow signing onto any agreement that would tie their own hands vis-à-vis disruptively interfering with physical cable infrastructure, whether for strategic, conflict, or domestic repression purposes. The United States could pursue such legal agreements in bilateral or limited multilateral capacities, such as within the NATO bloc, which could communicate a commitment from global, open internet countries to not disrupt submarine cables.

The Department of State should also conduct a study on ways to better integrate undersea cables into cyber capacity-building and foreign assistance programs for infrastructure worldwide, focused on security and resilience questions. Disruptions of undersea cables abroad can still undermine US economic and national security by cutting or slowing Internet connectivity to other parts of the world, and even hindering data flows to the United States. These cable disruptions can also undermine human rights, the free flow of information, and economic and national security in ally and partner countries. The Department of State should, therefore, conduct a study on ways to make this issue a more integral part of its cyber capacity-building and foreign assistance work with allies and partners. Options might include working with other governments to establish cable repair programs in their own countries, working with other governments and their private sectors to understand key risks to cable resilience, and working to ensure other governments are making fast repair and resilience requirements a key part of authorizing undersea cable construction within their jurisdictions. Boosting resilience in cable infrastructure can promote a more secure and global Internet for all.

US-based submarine cable owners should work with federal, state, and local authorities to establish public-private ISACs as threats to their submarine cable infrastructure grow. Industry-specific ISACs across sectors like health, energy, and finance have become integral mechanisms through which companies share cybersecurity threat information with other firms through established and confidential channels. Though many submarine cable owners are members of these and other ISACs, no ISAC exists specifically for threat sharing among submarine cable owners. Yet as more submarine cable owners deploy remote network management systems, directly connected to the Internet, to manage complex cable infrastructure, they are introducing new levels of cybersecurity risk: malicious actors could hack into these systems to disrupt cable signals. There are also many risks posed to cables that are distinct from those posed to other parts of those owners’ businesses (e.g., cloud platforms, cellular networks). US-based submarine cable owners should, therefore, establish ISACs where they can share cybersecurity threat information with one another to collectively protect submarine cable security and resilience and to increase their available intelligence for making corporate cybersecurity decisions. They should work as well with federal authorities, including the FCC and DHS, particularly the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), as well as state and local officials, to ensure the government also has requisite threat information to make determinations about particular cables that pose unique security risks or cables whose compromise would seriously undermine US economic and national security. That said, a key issue with threat sharing is liability. CISA’s liability protections for information sharing cover private firms giving information to DHS, but the federal government should consider expanded liability protections such that private companies can also share cable threat information with, at a minimum, those in the FCC, DOJ, and intelligence community that (in addition to DHS) are presently the driving force behind cable security reviews. Other factors can hinder threat sharing, such as a perceived lack of a business case for doing so, but this may be one way to help encourage it.

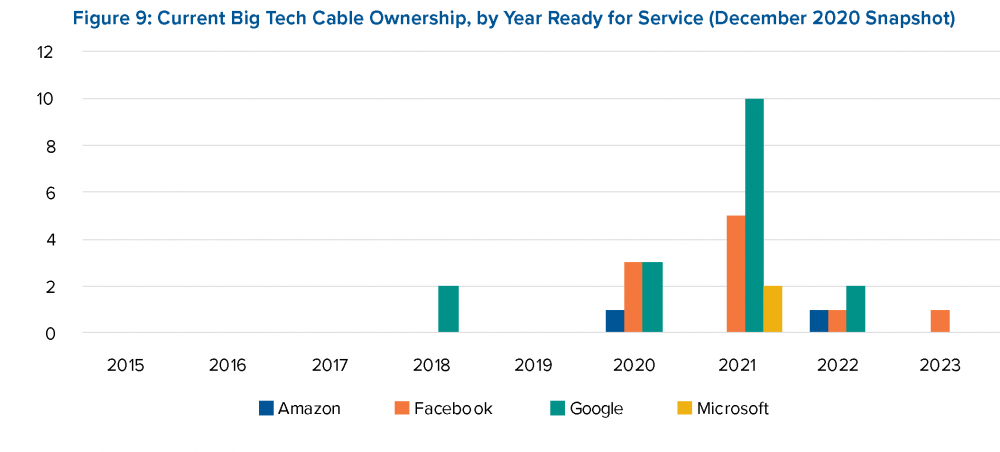

Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, whose investment in submarine cables worldwide is rapidly growing, should craft and publish strategies for protecting the security and resilience of their cable infrastructure. Information historically sent on back-end systems in energy, health, financial, defense, and transportation sectors is increasingly transmitted to and from the public cloud. These four US companies are also increasingly investing in building and maintaining the submarine cables which route that and other Internet data. As such, they have an elevated responsibility to protect these systems’ security and resilience: they have a direct ownership stake in the infrastructure and profit from it. Their increased focus on cable security and resilience should include such measures as greater investment in securing remote network management systems, greater investment in physically securing cable landing stations, more comprehensive plans for quickly repairing and restoring cables in the event of damage or disruption, and building and maintaining robust cable threat-sharing partnerships with one another, as well as with the US government and its allies and partners. (6)

For OODA Loop News Briefs on this topic, see Undersea Cables | OODA Loop.

https://oodaloop.com/archive/2022/09/28/russian-attack-on-undersea-energy-infrastructure-means-businesses-should-prepare-for-more-infrastructure-attacks-including-space-and-undersea-comms/

https://oodaloop.com/archive/2023/05/01/seven-crucial-global-power-shifts-displacements-risks-and-uncertainties-playing-out-in-sudan/

https://oodaloop.com/archive/2023/01/18/how-has-the-war-in-ukraine-changed-the-geopolitics-of-the-new-arctic/